|

Believers today

continue to dispute whether the Sabbath is

required. The Sabbath was given to Israel as

a covenant sign, and Israel was commanded to

rest on the seventh day. We see elsewhere in

the Old Testament that covenants have signs,

so that the sign of the Noahic covenant is

the rainbow (Gen. 9:8-17) and the sign of

the Abrahamic covenant is circumcision (Gen. 17). The paradigm for the Sabbath was God’s

rest on the seventh day of creation (Gen. 2:1-3). So, too, Israel was called upon to

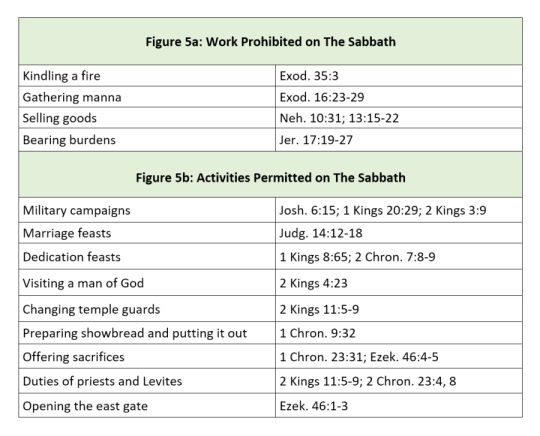

rest from work on the seventh day (Exod. 20:8-11; 31:12-17). What did it mean for

Israel not to work on the Sabbath? Figure 5

lists the kinds of activities that were

prohibited and permitted.

The Sabbath

was certainly a day for social concern, for

rest was mandated for all Israelites,

including their children, slaves, and even

animals (Deut. 5:14). It was also a day to

honor and worship the Lord. Special burnt

offerings were offered to the Lord on the

Sabbath (Num. 28:9-10). Psalm 92 is a

Sabbath song that voices praise to God for

his steadfast love and faithfulness. Israel

was called upon to observe the Sabbath in

remembrance of the Lord’s work in delivering

them as slaves from Egyptian bondage (Deut. 5:15). Thus, the Sabbath is tied to Israel’s

covenant with the Lord, for it celebrates

her liberation from slavery. The Sabbath,

then, is the sign of the covenant between

the Lord and Israel (Exod. 31:12-17; Ezek. 20:12-17). The Lord promised great blessing

to those who observed the Sabbath (Isa. 56:2, 6; 58:13-14). Breaking the Sabbath

command was no trivial matter, for the death

penalty was inflicted upon those who

intentionally violated it (Exod. 31:14-15; 35:2; Num. 15:32-36), though collecting

manna on the Sabbath before the Mosaic law

was codified did not warrant such a

punishment (Exod. 16:22-30). Israel

regularly violated the Sabbath—the sign of

the covenant—and this is one of the reasons

the people were sent into exile (Jer. 17:21-27; Ezek. 20:12-24).

During the

Second Temple period, views of the Sabbath

continued to develop. It is not my purpose

here to conduct a complete study. Rather, a

number of illustrations will be provided to

illustrate how seriously Jews took the

Sabbath. The Sabbath was a day of feasting

and therefore a day when fasting was not

appropriate (Jdt. 8:6; 1 Macc. 1:39, 45).

Initially, the Hasmoneans refused to fight

on the Sabbath, but after they were defeated

in battle, they changed their minds and

began to fight on the Sabbath (1 Macc.

2:32-41; cf. Josephus, Jewish Antiquities

12.274, 276-277). The author of Jubilees

propounds a rigorous view of the Sabbath

(Jubilees 50:6-13). He emphasizes that no

work should be done, specifying a number of

tasks that are prohibited (50:12-13).

Fasting is prohibited since the Sabbath is a

day for feasting (50:10, 12). Sexual

relations with one’s wife also are

prohibited (50:8), though offering the

sacrifices ordained in the law are permitted

(50:10). Those who violate the Sabbath

prescriptions should die (50:7, 13). The

Sabbath is eternal, and even the angels keep

it (2:17-24). Indeed, the angels kept the

Sabbath in heaven before it was established

on earth (2:30). All Jewish authors concur

that God commanded Israel to literally rest,

though it is not surprising that Philo

thinks of it as well in terms of resting in

God (Sobriety, 1:174) and in terms of having

thoughts of God that are fitting (Special

Laws, 2:260). Philo also explains the number

seven symbolically (Moses, 2:210).

The Qumran community was quite strict

regarding Sabbath observance, maintaining

that the right interpretation must be

followed (CD 6:18; 10:14- 23). Even if an

animal falls into a pit it should not be

helped on the Sabbath (CD 11:13-14),

something Jesus assumes is permissible when

talking to the Pharisees (Matt. 12:11). In

the Mishnah thirty-nine different types of

work are prohibited on the Sabbath (m.

Shabbat 7:2).

I do not believe the

Sabbath is required for believers now that

the new covenant has arrived in the person

of Jesus Christ. I should say, first of all,

that it is not my purpose to reiterate what

I wrote about the Sabbath in the Gospels

since the Sabbath texts were investigated

there. Here it is my purpose to pull the

threads together in terms of the validity of

the Sabbath for today. Strictly speaking,

Jesus does not clearly abolish the Sabbath,

nor does he violate its stipulations. Yet

the focus on regulations that is evident in

Jubilees, Qumran, and in the Mishnah is

absent in Jesus’ teaching. He reminded his

hearers that “the Sabbath was made for man,

not man for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27). Some

sectors of Judaism clearly had lost this

perspective, so that the Sabbath had lost

its humane dimension. They were so consumed

with rules that they had forgotten mercy

(Matt. 12:7). Jesus was grieved at the

hardness of the Pharisees’ hearts, for they

lacked love for those suffering (Mark 3:5).

Jesus’ observance of the Sabbath does

not constitute strong evidence for its

continuation in the new covenant. His

observance of the Sabbath makes excellent

sense, for he lived under the Old Testament

law. He was “born under the law” as Paul

says (Gal. 4:4). On the other hand, a

careful reading of the Gospel accounts

intimates that the Sabbath will not continue

to play a significant role. Jesus proclaims

as the Son of Man that he is the “lord even

of the Sabbath” (Mark 2:28). The Sabbath

does not rule over him, but he rules over

the Sabbath. He is the new David, the

Messiah, to whom the Sabbath and all the Old

Testament Scriptures point (Matt. 12:3-4).

Indeed, Jesus even claimed in John 5:17 that

he, like his Father, works on the Sabbath.

Working on the Sabbath, of course, is what

the Old Testament prohibits, but Jesus

claimed that he must work on the Sabbath

since he is equal with God (John 5:18).

It is interesting to consider here the

standpoint of the ruler of the synagogue in

Luke 13:10-17. He argued that Jesus should

heal on the other six days of the week and

not on the Sabbath. On one level this advice

seems quite reasonable, especially if the

strict views of the Sabbath that were common

in Judaism were correct. What is striking is

that Jesus deliberately healed on the

Sabbath. Healing is what he “ought” (dei) to

do on the Sabbath day (Luke 13:16). It seems

that he did so to demonstrate his

superiority to the Sabbath and to hint that

it is not in force forever. There may be a

suggestion in Luke 4:16-21 that Jesus

fulfills the Jubilee of the Old Testament

(Lev. 25). The rest and joy anticipated in

Jubilee is fulfilled in him, and hence the

rest and feasting of the Sabbath find their

climax in Jesus.

We would expect the

Sabbath to no longer be in force since it

was the covenant sign of the Mosaic

covenant, and, as I have argued elsewhere in

this book, it is clear that believers are no

longer under the Sinai covenant. Therefore,

they are no longer bound by the sign of the

covenant either. The Sabbath, as a covenant

sign, celebrated Israel’s deliverance from

Egypt, but the Exodus points forward,

according to New Testament writers, to

redemption in Christ. Believers in Christ

were not freed from Egypt, and hence the

covenant sign of Israel does not apply to

them.

It is clear in Paul’s letters

that the Sabbath is not binding upon

believers. In Colossians Paul identifies the

Sabbath as a shadow along with requirements

regarding foods, festivals, and the new moon

(Col. 2:16-17). The Sabbath, in other words,

points to Christ and is fulfilled in him.

The word for “shadow” (skia) that Paul uses

to describe the Sabbath is the same term the

author of Hebrews used to describe Old

Testament sacrifices. The law is only a

“shadow (skia) of the good things to come

instead of the true form of these realities”

(Heb. 10:1). The argument is remarkably

similar to what we see in Colossians: both

contrast elements of the law as a shadow

with the “substance” (sōma, Col. 2:17) or

the “form” (eikona, Heb. 10:1) found in

Christ. Paul does not denigrate the Sabbath.

He salutes its place in salvation history,

for, like the Old Testament sacrifices,

though not in precisely the same way, it

prepared the way for Christ. I know of no

one who thinks Old Testament sacrifices

should be instituted today; and when we

compare what Paul says about the Sabbath

with such sacrifices, it seems right to

conclude that he thinks the Sabbath is no

longer binding.

Some argue, however,

that “Sabbath” in Colossians 2:16 does not

refer to the weekly Sabbaths but only to

sabbatical years. But this is a rather

desperate expedient, for the most prominent

day in the Jewish calendar was the weekly

Sabbath. We know from secular sources that

it was the observance of the weekly Sabbath

that attracted the attention of Gentiles

(Juvenal, Satires 14.96-106; Tacitus,

Histories 5.4). Perhaps sabbatical years are

included here, but the weekly Sabbath should

not be excluded, for it would naturally come

to the mind of both Jewish and Gentile

readers. What Paul says here is remarkable,

for he lumps the Sabbath together with food

laws, festivals like Passover, and new

moons. All of these constitute shadows that

anticipate the coming of Christ. Very few

Christians think we must observe food laws,

Passover, and new moons. But if this is the

case, then it is difficult to see why the

Sabbath should be observed since it is

placed together with these other matters.

Another crucial text on the Sabbath is

Romans 14:5: “One person esteems one day as

better than another, while another esteems

all days alike. Each one should be fully

convinced in his own mind.” In Romans 14:1-15:6 Paul mainly discusses food that

some—almost certainly those influenced by

Old Testament food laws—think is defiled.

Paul clearly teaches, in contrast to

Leviticus 11:1-44 and Deuteronomy 14:3-21,

that all foods are clean (Rom. 14:14, 20)

since a new era of redemptive history has

dawned. In other words, Paul sides

theologically with the strong in the

argument, believing that all foods are

clean. He is concerned, however, that the

strong avoid injuring and damaging the weak.

The strong must respect the opinions of the

weak (Rom. 14:1) and avoid arguments with

them. Apparently the weak were not insisting

that food laws and the observance of days

were necessary for salvation, for if that

were the case they would be proclaiming

another gospel (cf. Gal. 1:8-9; 2:3-5; 4:10; 5:2-6), and Paul would not tolerate their

viewpoint. Probably the weak believed that

one would be a stronger Christian if one

kept food laws and observed days. The danger

for the weak was that they would judge the

strong (Rom. 14:3-4), and the danger for the

strong was that they would despise the weak

(Rom. 14:3, 10). In any case, the strong

seem to have had the upper hand in the Roman

congregations, for Paul was particularly

concerned that they not damage the weak.

Nevertheless, a crucial point must not

be overlooked. Even though Paul watches out

for the consciences of the weak, he holds

the viewpoint of the strong on both food

laws and days. John Barclay rightly argues

that Paul subtly (or not so discreetly!)

undermines the theological standpoint of the

weak since he argues that what one eats and

what days one observes are a matter of no

concern. [1] The Old Testament, on the other

hand, is clear on the matter. The foods one

eats and the days one observes are ordained

by God. He has given clear commands on both

of these issues. Hence, Paul’s argument is

that such laws are no longer valid since

believers are not under the Mosaic covenant.

Indeed, the freedom to believe that all days

are alike surely includes the Sabbath, for

the Sabbath naturally would spring to the

mind of Jewish readers since they kept the

Sabbath weekly.

Paul has no quarrel

with those who desire to set aside the

Sabbath as a special day, as long as they do

not require it for salvation or insist that

other believers agree with them. Those who

esteem the Sabbath as a special day are to

be honored for their point of view and

should not be despised or ridiculed. Others,

however, consider every day to be the same.

They do not think that any day is more

special than another. Those who think this

way are not to be judged as unspiritual.

Indeed, there is no doubt that Paul held

this opinion, since he was strong in faith

instead of being weak. It is crucial to

notice what is being said here. If the

notion that every day of the week is the

same is acceptable, and if it is Paul’s

opinion as well, then it follows that

Sabbath regulations are no longer binding.

The strong must not impose their convictions

on the weak and should be charitable to

those who hold a different opinion, but Paul

clearly has undermined the authority of the

Sabbath in principle, for he does not care

whether someone observes one day as special.

He leaves it entirely up to one’s personal

opinion. But if the Sabbath of the Old

Testament were still in force, Paul could

never say this, for the Old Testament makes

incredibly strong statements about those who

violate the Sabbath, and the death penalty

is even required in some instances. Paul is

living under a different dispensation, that

is, a different covenant, for now he says it

does not matter whether one observes one day

out of seven as a Sabbath.

Some argue

against what is defended here by appealing

to the creation order. As noted above, the

Sabbath for Israel is patterned after God’s

creation of the world in seven days. What is

instructive, however, is that the New

Testament never appeals to Creation to

defend the Sabbath. Jesus appealed to the

creation order to support his view that

marriage is between one man and one woman

for life (Mark 10:2-12). Paul grounded his

opposition to women teaching or exercising

authority over men in the creation order (1 Tim. 2:12-13), and homosexuality is

prohibited because it is contrary to nature

(Rom.1:26-27), in essence, to God’s

intention when he created men and women.

Similarly, those who ban believers from

eating certain foods and from marriage are

wrong because both food and marriage are

rooted in God’s good creation (1 Tim. 4:3-5). We see nothing similar with the

Sabbath. Never does the New Testament ground

it in the created order. Instead, we have

very clear verses that say it is a “shadow”

and that it does not matter whether

believers observe it. So, how do we explain

the appeal to creation with reference to the

Sabbath? It is probably best to see creation

as an analogy instead of as a ground. The

Sabbath was the sign of the Mosaic covenant,

and since the covenant has passed away, so

has the covenant sign.

Now it does

not follow from this that the Sabbath has no

significance for believers. It is a shadow,

as Paul said, of the substance that is now

ours in Christ. The Sabbath’s role as a

shadow is best explicated by Hebrews, even

if Hebrews does not use the word for

“shadow” in terms of the Sabbath. The author

of Hebrews sees the Sabbath as foreshadowing

the eschatological rest of the people of God

(Heb. 4:1-10). A “Sabbath rest” still awaits

God’s people (v. 9), and it will be

fulfilled on the final day when believers

rest from earthly labors. The Sabbath, then,

points to the final rest of the people of

God. But since there is an

already-but-not-yet character to what

Hebrews says about rest, should believers

continue to practice the Sabbath as long as

they are in the not-yet?

[2] I would answer

in the negative, for the evidence we have in

the New Testament points in the contrary

direction. We remember that the Sabbath is

placed together with food laws and new moons

and Passover in Colossians 2:16, but there

is no reason to think that we should observe

food laws, Passover, and new moons before

the consummation. Paul’s argument is that

believers now belong to the age to come and

the requirements of the old covenant are no

longer binding.

Does the Lord’s Day,

that is, Christians worshiping on the first

day of the week, constitute a fulfillment of

the Sabbath? The references to the Lord’s

Day in the New Testament are sparse. In

Troas believers gathered “on the first day

of the week . . . to break bread” and they

heard a long message from Paul (Acts 20:7).

Paul commands the Corinthians to set aside

money for the poor “on the first day of

every week” (1 Cor. 16:2). John heard a loud

voice speaking to him “on the Lord’s day”

(Rev. 1:10). These scattered hints suggest

that the early Christians at some point

began to worship on the first day of the

week. The practice probably has its roots in

the resurrection of Jesus, for he appeared

to his disciples “the first day of the week”

(John 20:19). All the Synoptics emphasize

that Jesus rose on the first day of the

week, i.e., Sunday: “very early on the first

day of the week” (Mark 16:2; cf. Matt. 28:1;

Luke 24:1). The fact that each of the

Gospels stresses that Jesus was raised on

the first day of the week is striking. But

we have no indication that the Lord’s Day

functions as a fulfillment of the Sabbath.

It is likely that gathering together on the

Lord’s Day stems from the earliest church,

for we see no debate on the issue in church

history, which is quite unlikely if the

practice originated in Gentile churches

outside Israel. By way of contrast, we think

of the intense debate in the first few

centuries on the date of Easter. No such

debate exists regarding the Lord’s Day.

The early roots of the Lord’s Day are

verified by the universal practice of the

Lord’s Day in Gentile churches in the second

century. [3] It is not surprising that many

Jewish Christians continued to observe the

Sabbath as well. One segment of the Ebionites practiced the Lord’s Day and the

Sabbath. Their observance of both is

instructive, for it shows that the Lord’s

Day was not viewed as the fulfillment of the

Sabbath but as a separate day.

Most

of the early church fathers did not practice

or defend literal Sabbath observance (cf.

Diognetus 4:1) but interpreted the Sabbath

eschatologically and spiritually. They did

not see the Lord’s Day as a replacement of

the Sabbath but as a unique day. For

instance, in the Epistle of Barnabas, the

Sabbaths of Israel are contrasted with “the

eighth day” (15:8), and the latter is

described as “a beginning of another world.”

Barnabas says that “we keep the eighth day”

(which is Sunday), for it is “the day also

on which Jesus rose again from the dead”

(15:9). The Lord’s Day was not viewed as a

day in which believers abstained from work,

as was the case with the Sabbath. Instead,

it was a day in which most believers were

required to work, but they took time in the

day to meet together in order to worship the

Lord. [4] The contrast between the Sabbath

and the Lord’s Day is clear in Ignatius,

when he says, “If, therefore, those who were

brought up in the ancient order of things

have come to the possession of a new hope,

no longer observing the Sabbath, but living

in the observance of the Lord’s Day, on

which also our life has sprung up again by

Him and by His death” (To the Magnesians

9:1). Ignatius, writing about A.D. 110,

specifically contrasts the Sabbath with the

Lord’s Day, showing that he did not believe

the latter replaced the former.

[5] Bauckham

argues that the idea that the Lord’s day

replaced the Sabbath is post-Constantinian.

Luther saw rest as necessary but did not tie

it to Sunday. [6] A stricter interpretation

of the Sabbath became more common with the

Puritans, along with the Seventh-Day

Baptists and later the Seventh-day

Adventists. [7]

SUMMARY

Believers are not obligated to observe the

Sabbath. The Sabbath was the sign of the

Mosaic covenant. The Mosaic covenant and the

Sabbath as the covenant sign are no longer

applicable now that the new covenant of

Jesus Christ has come. Believers are called

upon to honor and respect those who think

the Sabbath is still mandatory for

believers. But if one argues that the

Sabbath is required for salvation, such a

teaching is contrary to the gospel and

should be resisted forcefully. In any case,

Paul makes it clear in both Romans 14:5 and

Colossians 2:16-17 that the Sabbath has

passed away now that Christ has come. It is

wise naturally for believers to rest, and

hence one principle that could be derived

from the Sabbath is that believers should

regularly rest. But the New Testament does

not specify when that rest should take

place, nor does it set forth a period of

time when that rest should occur. We must

remember that the early Christians were

required to work on Sundays. They worshiped

the Lord on the Lord’s Day, the day of

Jesus’ resurrection, but the early

Christians did not believe the Lord’s Day

fulfilled or replaced the Sabbath. The

Sabbath pointed toward eschatological rest

in Christ, which believers enjoy in part now

and will enjoy fully on the Last Day.

|

Footnotes

1. John M. G. Barclay, “‘Do We Undermine the

Law?’ A Study of Romans 14.1-15.6,” in Paul

and the Mosaic Law, WUNT 89 (Tübingen: Mohr

Siebeck, 1996), 287-308.

2. So Richard B.

Gaffin, Jr., “A Sabbath Rest Still Awaits

the People of God,” in Pressing Toward the

Mark: Essays Commemorating Fifty Years of

the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, ed.

Charles G. Dennison and Richard C. Gamble

(Philadelphia: The Committee for the

Historian of the Orthodox Presbyterian

Church, 1986), 33-51. Gaffin argues that the

rest is only eschatological. I support

Andrew Lincoln’s view that it is of an

already-but-not-yet character (Andrew T.

Lincoln, “Sabbath, Rest, and Eschatology in

the New Testament,” in From Sabbath to

Lord’s Day: A Biblical, Historical, and

Theological Investigation, ed. D. A. Carson

[Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1982], 197-220).

3. For a detailed discussion of some of the

issues raised here, see R. J. Bauckham, “The

Lord’s Day,” in From Sabbath to Lord’s Day:

A Biblical, Historical, and Theological

Investigation, ed. D. A. Carson (Grand

Rapids: Zondervan, 1982), 221-50; idem,

“Sabbath and Sunday in the Post-Apostolic

Church,” in From Sabbath to Lord’s Day,

257-69.

4. So Bauckham, “Sabbath and

Sunday in the Post-Apostolic Church,” 274.

5. Cf. the concluding comments of Bauckham,

“The Lord’s Day,” 240.

6. Martin Luther,

“How Christians Should Regard Moses,” in

Luther’s Works, vol. 35, Word and Sacrament,

ed. Helmut T. Lehmann (general editor) and

E. Theodore Bachman (Philadelphia:

Muhlenberg Press, 1960), 165.

7.

Bauckham’s survey of history is immensely

valuable. See Bauckham, “Sabbath and Sunday

in the Post-Apostolic Church,” 251-98; idem,

“Sabbath and Sunday in the Medieval Church

in the West,” in From Sabbath to Lord’s Day,

299-309; idem, “Sabbath and Sunday in the

Protestant Tradition,” in From Sabbath to

Lord’s Day, 311-41.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Taken

from 40 Questions on Christians and Biblical

Law © copyright 2010 by Thomas R. Schreiner.

Published by Kregel Publications, Grand

Rapids, MI. Used by permission of the

publisher. All rights reserved.

|